With heavy hearts we share the loss of Aldo Parisot, extraordinary performer and beloved pedagogue. A legendary figure in the music world, he was the longest-serving member in history at the Yale School of Music, mentoring and inspiring young artists for the past 60 years. At the age of 99, this past June, he retired from teaching.

Acknowledged as one of the world’s master cellists, Mr. Parisot led the career of a complete and well-rounded artist as concert soloist, chamber musician, recitalist, and devoted teacher. He was heard with many of the major orchestras of the world, including Berlin, London, Paris, Amsterdam, Stockholm, Rio, Munich, Warsaw, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Pittsburgh, under the batons of such eminent conductors as Stokowski, Barbirolli, Bernstein, Mehta, Monteux, Paray, de Carvalho, Sawallisch, Hindemith, and Villa-Lobos.

As an artist seeking to expand the cello repertoire, Mr. Parisot premiered numerous works for the cello written especially for him by such composers as Carmago Guarnieri, Quincy Porter, Alvin Etler, Claudio Santoro, Joan Panetti, Ezra Laderman, Yehudi Wyner, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, whose Cello Concerto No. 2, written for and dedicated to him, was premiered by Parisot in his New York Philharmonic debut.

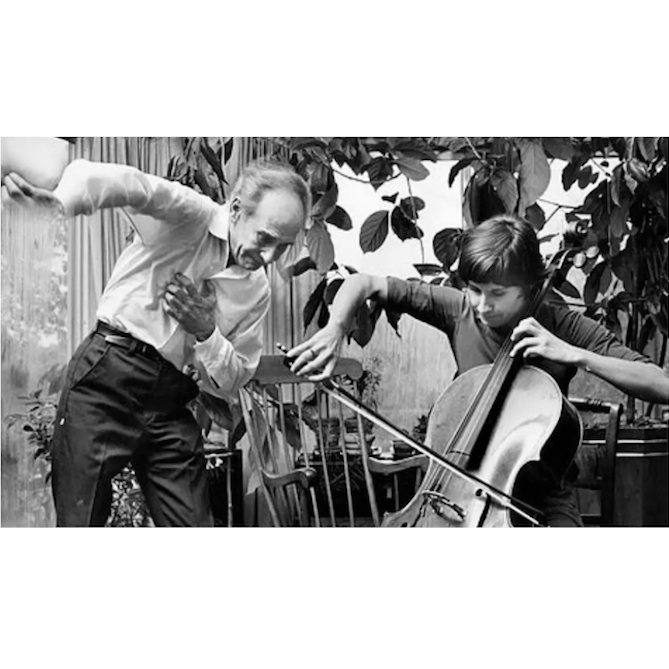

Beyond his contributions as a performer, Mr. Parisot’s devotion to teaching and the well-being of his students was profound. In a 2017 Yale School of Music Interview he shared “I have great, great joy in teaching these people, they are my children…I see in them me, when I was young, and I want to see them succeed. I am very severe because I care about them. I teach my students, ‘Your future depends on you. You’ve got to believe in yourself. You can do it. But only you can do it. I can only help you.'” He continued “I try to make students believe in themselves and that includes without the cello.”

János Starker, one of Mr. Parisot’s dear friends over the course of many years, described Parisot as “The best cello teacher of our time.”

The profound impact his presence has had on the lives of many artists elicits reflections and personal tributes. These reflections and tributes will be featured below as we continue to receive them over the course of the next few days.

CelloBello would like to invite all former students and friends of Mr. Parisot to contribute to this tribute. Please send your reflections to our Blog Master at jamie@cellobello.org.

——————

From Jian Wang:

I met Mr. Parisot when I was 14. After one lesson I wanted to study with him. My father who taught me the cello from the beginning agreed, saying that Mr. Parisot was one of the teachers who were more interested in making his students a better version of themselves, rather then to make them a poor version of the teacher. Having taught for 60 years, he perhaps has one of the largest amount of students around the world, and none of us play alike. You can never tell who studied with Aldo Parisot, in my opinion, that is the biggest compliment a teacher can have.

I studied with him for 7 years, 3 at Yale and 4 at Juilliard. He liked to say he went to Juilliard because of me, another example how he always looked for ways to make people feel good about themselves. I learned every thing about the cello playing from him, also how to be a performer… Being one of the most successful soloists of his time, he had an incredible amount of experiences to draw from to enlighten us. Over the years he became like a father to me. If there is one word I can describe him, it would be generosity. He was generous to everyone he met, the reason he could be like that was his natural tendency to always focus on the good part of people, almost consciously ignoring the bad part. One of his favorite sentences was that One thing has nothing to do with the other… A catch phrase of someone who is willing to give a fresh start to anyone, even someone who had hurt him…

Later in life, he said to me that the walk to stage is a lonely one, because even God would stay behind the curtain and leave you alone. But he will always be there, to make sure I play in tune… I hope he keeps his promise… With all my heart…

——————

From Robert deMaine:

Aldo, or Mr. Parisot, as I still call him, was, for me, the ideal teacher -and even prophet – for me at that time in my life. He gave me a big dose of reality – tough love – and the lessons he taught me ring even more true the older I get, which perhaps is the greatest gift of all, and for me that is the rarest, most precious quality of great educators.

(In my mind, a significant part of Mr. Parisot’s approach was the cultivation of a studio just bursting with talent, which was a gigantic inspiration to all of us. We in that collection of cellists learned so much from one another; it cannot have been accidental.)

Thank you, Mr. Parisot.

——————

From Carter Brey:

The last time I saw Aldo Parisot was many decades after my year of studying with him as a graduate student at Yale University in the late 1970’s. Emerging unexpectedly from the elevator in the lobby of the music school at Yale where I had been rehearsing for some upcoming concerts, he stopped and surveyed me through his thick glasses, a faint smirk spreading across his features as he took in my receding hairline and weatherbeaten face. I was well into middle age and he was already a nonagenarian, still vigorous, self-aware and alert despite the cane on which he lightly leaned. “How old are you?” he finally asked, like a baffled tourist inquiring about the patina of age on the Pantheon. “I’ve decided to remain sixty years old,” he continued in a satisfied tone, as if he had discovered the solution to the problem of mortality and all that remained was to put the plan into effect.

All of us in the community of cellists and the wider musical world were taken aback by the news of Aldo’s demise. It had indeed begun to seem that he was destined to continue indefinitely. I suppose that his retirement this year after sixty years on the Yale faculty was a signal that even this remarkable man was not proof against the natural order of things on this earth.

I was fortunate enough to take lessons with him for a year as a 23-year-old music student at Yale. Back then the School of Music was housed in Stoeckel Hall, a Venetian-Gothic pile located strategically close to a pizzeria where musical and political issues were thrashed out amid a hogo of beer suds and tomato sauce. Aldo’s studio was upstairs; you knocked at the appointed hour and opened the door to a scene of Stygian gloom. An eye condition which required him always to wear dark glasses when outside meant that, in his studio, illumination was restricted to a wan circle of light from a single floor lamp placed near the student’s chair. Aldo’s precise location was determined by the glow from the end of the cigarette which he had always in one hand in those days.

This smoking habit, without which I have to assume Aldo would have gone on to celebrate a second rather than a mere single centenary, bears further discussion. In the course of a lesson he would customarily sit at his cello opposite me, a Dunhill smoldering in a holder held between the second and third fingers of his right hand– his bow hand. As I labored at the Dvorak Concerto or a Duport etude, Aldo would remain absolutely motionless. His attention thus directed entirely at me, the ash on the neglected cigarette would grow to amazing lengths. Much as I tried I could not help watching this progression out of the corner of my eye, because I knew what would happen next. As soon as I stopped playing, Aldo would commence his commentary and lift his bow to begin a demonstration. The sudden disturbance would precipitate the ash from the end of the Dunhill, whence it would fall onto the top of his cello to disperse in graceful eddies and disappear down the F-holes into its interior. This was no ordinary cello. It was the “De Munck” Stradivarius, which had belonged to the legendary Emanuel Feuermann until his death in 1942.

Aldo Parisot’s teaching style was not based on the transmission of a grand, overarching view of music. Neither was it greatly concerned with historical detail. It was practical, reactive and prescriptive. A fabulous diagnostician, he could watch a student play and summarize succinctly his or her technical weaknesses, offering solutions to problems and stylistic suggestions informed by his years as a virtuoso. Being part of his class was like attending the highest-level finishing school imaginable, none of us sounding like anyone else and above all none of us sounding like him. His intent was to discover who each of us was and to make it possible for that person to realize his or her musical personality without obstacles. I believe the idea of mass-producing versions of himself would have filled him with horror.

There are so many of us now, former Parisot students. We encounter each other in orchestras, at chamber music festivals, at conservatories and in university music departments, a widely-disseminated community of cellists, “Parisites,” as we fondly refer to each other. “Oh! You studied with Aldo, too?” we ask each other. And then we smile and begin to reminisce.

——————

From Ralph Kirshbaum:

While we mourn the passing of this exceptional man, we should at the same time celebrate Aldo Parisot’s extraordinary life which, through his excellence as a cellist, musician, and teacher—each role infused with a seemingly limitless supply of love, joy, generosity, warmth, passion, impish humor, and fierce loyalty— touched so many lives around the world.

Cello Teacher with the License to Dazzle – printed in the New York Times – April 17, 2009

“FOGO.” Some enigmatic expletive? Actually, fogo is the Portuguese word for fire.

One of my earliest memories of Aldo Parisot is of his red Karmann Ghia, bearing a Connecticut license plate with the personalized inscription “FOGO.” It seemed incongruous: this soft-spoken Brazilian gentleman with the fiery-red sports car, zipping through the country roads surrounding the tranquil village of Norfolk, Conn., where we first met at the Yale Summer School of Music and Art.

That was in July 1964, and I soon came to realize that the connotations of fogo — passion, ebullient color — spoke to the heart and soul of Mr. Parisot, as man, artist and teacher. Today, at 87, he is as full of fire, instinctive wisdom and irreverent humor as he was then.

On Tuesday as part of the series Yale in New York, Mr. Parisot will be surrounded by another generation of students, the latest roster of the internationally recognized Yale Cellos, which he formed in 1983. Though he rarely opens himself up to public adulation, this concert at Zankel Hall will celebrate 25 seasons of the Yale Cellos and 50 years of Mr. Parisot’s outstanding achievement as a cello professor at Yale.

As I was fortunate to discover in four stimulating years of study with Mr. Parisot, he is full of contrast but not contradiction: quiet yet bold in his pronouncements; flexible yet demanding; conservative in dress and palate (chicken and rice for dinner four or five nights a week) yet liberal in musical phrasing and color; intolerant of any perceived injustice yet embracing of individuals irrespective of race, creed, color or nationality.

We laugh together today at my stubbornness as his pupil. His inherent judgment and humor were always up to the challenge. If, for example, I obstinately rejected a suggested fingering or bowing, he would send me away to master four versions of the same phrase; only then, he counseled, would I have the right to make an informed choice. And when I returned from winning a competition, he cautioned: “Don’t get a big head. It is just a drop in the bucket.”

Janos Starker, the celebrated Hungarian-born cellist who has taught with great distinction for more than 50 years at Indiana University, said recently: “Aldo Parisot is the best cello teacher I have met in my life. He marvelously combines issues of mechanical problems with musical and performing details.”

The two met in 1956, attending each other’s recitals in Wigmore Hall in London. After Mr. Parisot’s performance, Mr. Starker asked him, “Why do you play Bach so Romantically?” Mr. Parisot retorted, “Why do you play it so dry?” Thus was a friendship born.

Aldo Parisot was born in Natal, the capital of the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Norte, in 1921. His mother, a church organist, lived to 102. His father, who died when Aldo was 4, was an engineer, involved in building roads.

How did Aldo come to the cello? As fate would have it, a fine cellist, Thomazzo Babini, moved to Natal in about 1915 to teach at the local conservatory. Some years later, after the death of Aldo’s father, his mother married Babini. So at 5, an ideal age to start, Aldo Parisot took up the cello.

He recalls his stepfather as having been an outstanding teacher. Little wonder that Aldo’s half brother, Italo Babini, developed into a highly accomplished cellist as well; for many years he was the principal cellist of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra.

From a young age fire and passion burned brightly in Aldo Parisot. He defied convention and the authorities, manipulating the truth about his age to serve a year in the army and free himself to get on with his career.

He played in a local chamber orchestra, which recorded three 30-minute programs a week for radio broadcast. In addition he recorded a 30-minute cello recital each week, covering movements of concertos, virtuoso pieces and Classical and Baroque sonatas. This excellent training gave Mr. Parisot a sense of discipline that was to become a dominant theme in his life.

Not surprisingly, his aspirations grew. The United States beckoned. Sadly, he was denied the opportunity to study with his boyhood idol, Emanuel Feuermann, who died at 39 in 1942, three months before Mr. Parisot was to begin studies with him at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. Finally, in 1946, Mr. Parisot went to New Haven as a special student at Yale. (No cello lessons.) Feuermann’s artistry and technical perfection remained the benchmark for him both in his playing and, eventually, in the development of his students.

Mr. Parisot later became the proud owner of the Feuermann Stradivarius cello, his beloved companion through much of his solo career. He performed with orchestras around the world and made numerous appearances with the New York Philharmonic.

One exceptional series of concerts at the Philharmonic in 1960 featured Paul Hindemith’s Cello Concerto conducted by Hindemith, whom Mr. Parisot recently pithily described as “a miserable conductor but a great composer.” Some years earlier, as a young, quick-tempered principal cellist of the New Haven Symphony Orchestra, he had had a run-in with Hindemith.

With an apprehension fueled by this memory, Mr. Parisot met privately with Hindemith before the first Philharmonic rehearsal. He played through the concerto with every nuance in place, thanks to six months of feverish and exacting practice. After complimenting him on his perfect playing, Hindemith added, “But Parisot, why don’t you play it the way you really feel it.”

Freed from his self-imposed straitjacket, he did just that. Freedom, color and instinctive phrasing were all hallmarks of Mr. Parisot’s playing. When he played Donald Martino’s “Parisonatina al’Dodecafonia,” one of many works written for him, at Tanglewood in 1966, the reviewer for The Boston Globe wrote, “There is probably no cellist that can equal Parisot’s dazzling achievement.”

He continued to perform for another 20 years, though at a less hectic pace. He wanted to spend time with his three young sons by Ellen Lewis, his former wife, and he began to cancel concerts. “Managers hated me,” he said. An exaggeration, no doubt, but a typically strong and forthright Parisot observation.

So is his explanation of why, in 1988, he decided to stop performing altogether. “My fingers were no longer fast enough,” he said. “I wasn’t as good as I wanted to be.”

With equal candor he described himself, in his early years of teaching, as dogmatic. “But I realized this wasn’t productive,” he added, “so I changed.”

There is no question that Mr. Parisot’s directness and impulsive statements, uncensored by political correctness, have at times ruffled feathers. But in my experience heartfelt issues and principles have always been apparent beneath any outburst; his reactions are never capricious. He protects and supports his cellistic offspring in every way, in equal measure and without any sense of favoritism. He radiates warmth, personal charm and an impish sense of humor.

While I was studying at Yale, he announced one morning that he was expecting a call from Broadus Erle, his friend and the head of violin studies at the university. Ten minutes later the phone rang, and a very excited Erle told Mr. Parisot of an audition tape he had just received from a phenomenal violinist named David Weiss. On it Weiss performed the notoriously difficult 24th Caprice of Paganini flawlessly, in a manner worthy of Heifetz. Erle couldn’t wait to have him as a pupil.

Mr. Parisot hung up the phone and burst out laughing, tears streaming beneath his omnipresent dark glasses. He had made the tape, at half speed on the cello, to sound like a violin when played at full speed. The name David Weiss was a play on the name of the viola professor at Yale, David Schwartz.

Around the same time, a new dimension unfolded in Mr. Parisot’s life. He visited a student art exhibition in Norfolk and was captivated. He bought basic materials and began to paint. A succession of eminent art lecturers who came to Norfolk told him that he had a good sense of color and rhythm. (His favorite artist is Paul Klee.) They also told him, “Don’t study, just paint.”

He has followed that advice and completed more than 3,000 paintings in an ever developing range of styles. He has been exhibited, but he chooses to sell only at Yale Cellos concerts and special events, devoting the proceeds to a travel fund for deserving students. He has so far raised almost half a million dollars.

With this characteristic generosity he also discreetly helps students in need. He inspires his pupils, prods them, cajoles them, counsels them. In all of this he is enthusiastically supported by his wife, the pianist Elizabeth Sawyer Parisot, who accompanies his students in classes, auditions and concerts, and is always a cheerful and encouraging presence.

“The secret to staying young,” Mr. Parisot says, “is to surround yourself with the younger generation. It is boring to talk to the elderly about their blood pressure and cholesterol levels.”

——————

From Inbal Megiddo:

It was the summer after completing my undergraduate at Yale, just before starting my Master’s program at the Yale School of Music when it happened. I was staying in New Haven for part of it and taking some extra lessons with Mr. Parisot over the summer. Convinced I was invincible, as only 20-year-olds can be, I decided to go hang-gliding one day, crashed (quite spectacularly), and severely broke my left arm. It was a huge shock and felt like the end of the world. It took me two weeks to gather courage to call Mr. Parisot and let him know. I dialed the numbers, convinced he would be furious about my stupidity; that I would be kicked out of his studio until I could play again. The phone rang and his familiar croak came over the phone.

“Halloo?”

“Mr. Parisot… I have some bad news…”

“What happened?”

“I… broke my arm.”

“Oh, thank goodness! I thought it was something serious!”

As always, he knew the right thing to say. And then, despite my not being able to play for over six months, Mr. Parisot kept me as a student and continued to have me come for my weekly lessons. Sometimes we would work on the bow arm, and other times we would have long talks about music and life. (He told me that he broke his arm climbing a mango tree in his small town in Natal, Brazil. The doctor set the bone with an inner tube of a tire. Soon after, he started playing soccer before it was fully healed and broke it again!) With no family nearby, when it came time for me to have surgery, I stayed with the Parisots while healing. I then had to relearn all of my left-hand technique.

My first encounter with Mr. Parisot occurred when I was twelve, at the Jerusalem Music Center when I played for him in a masterclass. At the time, he was still a chain smoker and held a lit cigarette during the entire class. When he held my arm to show me a gesture, the cigarette burned a hole through my favorite sweater! He spoke about circles, breathing, phrasing, colors, and passion. I wasn’t sure what it all meant, but it was thrilling! I knew then that I wanted to go and study with him and find out. Five years later, I got my wish when I was accepted into his studio as a Yale undergraduate. I spent eight years at Yale with him for my undergraduate and postgraduate degrees; one year extra because of the broken arm.

My first semester with him was exhilarating and terrifying. As the only undergraduate and a young one at that, the other students seemed to me to basically be adults and all were incredible cellists. I was thoroughly intimidated. In my first lesson, he heard me play a little and then said, “why don’t you play in cello class next week? How about the Haydn D major?” I’d never played that concerto before, but I wasn’t about to say I couldn’t do it. I went to my dorm room and worked like a maniac, and the next Tuesday morning, played it in class. And with that experience, I found my confidence and my place in the class. Mr. Parisot was still smoking that first semester, and with his sensitivity to light, the studio was perpetually dark and cloudy, so any piece you played had to be mostly memorized. And then you would come outside to the fresh air and other students would smell the smoke and say, “oh, you must have just had a lesson!”

He taught us to play the cello phenomenally well. He knew everything about technique. Incredible bow technique that allows you to draw out maximum sound and colors from the instrument; his ideas of shifting that help with accuracy but are also tools to create and phrase; and his philosophy of timing, of how to push and pull within the pulse of a piece. He knew how to draw out from each student their unique voice. And that is probably his most remarkable gift as a pedagogue. None of his students sound the same. Or perhaps, the similarity is in the freedom they all have, both technically and musically.

But Mr. Parisot was so much more than a teacher of cello. He taught me an approach to life. And while I was at Yale only for eight years, up until just last month, whenever I was facing a dilemma – career related, music, or personal, I would call and he was always ready with advice, wisdom, and support. And you could count on that advice to be honest – sometimes harsh, but always what you needed to hear.

In my second year of graduate school, Mr. Parisot decided it was time I had my official debut in New York. I worked with him closely to choose the repertoire, and then he picked up the phone and used his connections – first to get me a suitably high quality cello for the debut, and then to bring in fantastic musicians to join me: the incredible Ben Verdery on guitar for de Falla’s Suite Populaire Espagnole, and the wonderful David Stern to conduct the orchestra for the Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations and Radzynski Cello Concerto. After months of preparation the big day came. Mr. P came backstage, took my cello and slipped a dollar bill in through the F hole. “This is for good luck!” To this day, every time I take my cello to a new luthier they hear the odd rattle inside, and I tell them that whatever they need to do to the cello, they better not remove that dollar bill! It has provided years of good luck!

With his usual generosity, when I decided to research and write about his teaching methods, he opened up his studio and home to me. Over the last few years I was able to observe hundreds of hours of his teaching and interview him about his theories and method. It is one thing to have gone through it as a student myself, but to observe how he approached different students and different concepts was a rare and fascinating experience and I am looking forward to sharing the results of my research. I, along with his many other students, hold a precious legacy to pass on to the next generations.

Even though he was 100, it was still a shock to hear the sad news of his passing. He was so full of life, vitality, joy, and passion, it felt like he would live forever. Though he is gone, his artistry, his vivacity, his irreverence, his humor, his music, and his love, through his many many students, will continue to fill our world.