100 Cello Warm-Ups and Exercises Blog 7: Open String Warm-Ups Part 1

Robert Jesselson

On most days I like to warm up with open strings. I love the sound of the open strings, and the feeling of the natural vibrations against my chest. I like to listen to the fundamental pitch, and then try to hear some of the overtones that make the tone color – a pure sound which connects me back to the earliest sounds of music, the aural “ur-sound” of the first stringed instrument played by a human being. I can hear the lyra or the rabab, or back still further to the plucked sounds of the lyre, or even earlier to the first time someone plucked the string on a bow and arrow. I can hear the rebec, the gamba, or the arpeggione, or a hundred other ancestors and close relatives to our cello. It’s a great way to start the day. Playing open strings can bring me quickly from the hustle and bustle of the outside world into the cello world. It helps me to settle down, breathe, focus and concentrate on the tasks at hand. It is my way of saying “om”, a kind of cello mantra that leads me into a healthy and creative place for practicing and making music. It may seem totally obvious to start with open strings, but at the risk of sounding obvious I suggest starting every day by going back to the basics:

On most days I like to warm up with open strings. I love the sound of the open strings, and the feeling of the natural vibrations against my chest. I like to listen to the fundamental pitch, and then try to hear some of the overtones that make the tone color – a pure sound which connects me back to the earliest sounds of music, the aural “ur-sound” of the first stringed instrument played by a human being. I can hear the lyra or the rabab, or back still further to the plucked sounds of the lyre, or even earlier to the first time someone plucked the string on a bow and arrow. I can hear the rebec, the gamba, or the arpeggione, or a hundred other ancestors and close relatives to our cello. It’s a great way to start the day. Playing open strings can bring me quickly from the hustle and bustle of the outside world into the cello world. It helps me to settle down, breathe, focus and concentrate on the tasks at hand. It is my way of saying “om”, a kind of cello mantra that leads me into a healthy and creative place for practicing and making music. It may seem totally obvious to start with open strings, but at the risk of sounding obvious I suggest starting every day by going back to the basics:

Other things to think about while doing the open strings include: breathing, relaxation of the shoulders at the frog, the “front and back of the hand”, and of course just listening to the sound. As I mentioned in the video, I like to use contrary motion, or left/right motion– I discussed that in Blog #5 on Balance. I usually do the open strings as close to the bridge as possible, but staying as relaxed as possible. We are told that Corelli used to audition violinists for his ensembles in 1700 by asking them to hold a stopped third for 15 seconds in one bow. So apparently playing with a slow bow close to the bridge was important way back in the Baroque! Of course violinists have a longer bow than cellists, but our modern bows are longer than Baroque bows. It is difficult enough to hold an open G string for 15 seconds – but try it with a double-stop third! And this is not an “idle” exercise – we often need a slow bow in order to play lots of notes in a bow with son filé technique. Many of the Popper etudes require this technique as a “given”, despite the fact that they are mostly working on left hand issues.

Exercise for Changing the Bow Angle to Raise or Lower the Contact Point: Once the bow angle is consistently parallel to the bridge and the contact point is steady, it is useful to practice changing the contact point in order to change the volume or tone color within one long bow stroke. We can do this in two ways: either by moving the arm up or down, or by changing the bow angle on purpose, making the bow slide up or down as needed.

There are lots of different approaches to bow technique. In this series of warm-ups and exercises I am not advocating for any particular school of thought in these warm-up exercises. I think that most of the exercises will be applicable to most bow techniques. After all, our goal is to produce a good sound in as easy a way as possible. My background, through my teachers in Europe, is the French bow technique that I learned from Marcal Cervera and Paul Tortelier, enhanced by my graduate study work with Paul Katz and Bernie Greenhouse. I love Paul’s story about the fingers as sailors on a boat, describing the placement of the different fingers on the bow – I remember him telling me that story in a lesson almost 40 years ago, and I use it with all my new students. (http://www.cellobello.org/lessons/20 )

I also like to think about the function of each of the fingers on the bow, and assign each one a special task:

First finger – transfers the arm weight into the bow

Second Finger – anchor finger

Third Finger – rotation, and centering finger

Fourth Finger (little finger) – balance Thumb – Counter-balance; guide finger

Here are some exercises, in no particular order, that I do with the open strings – I certainly don’t do all of them every day, but I rotate around doing different ones on different days.

The “Getting into the String” Exercise: This exercise is useful for reminding ourselves that almost every stroke starts from the string:

Down-bow Exercise: This exercise checks to make sure that the bow angle is consistently parallel to the bridge by using a fast bow speed and high contact point

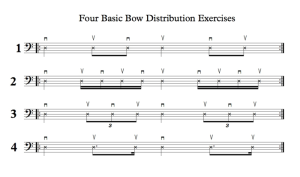

Four Basic Bow Distribution Exercises:

There are four basic bow distribution exercises that l like to do with my students. They are:

Next week’s Blog (#8) will continue with lots of open string warm-ups, such as the “Bubble Exercise”, the “Bouncy Bow Exercise”, string crossings, bow changes, the “front and back of the hand”, exercises changing dynamics, and bow vibrato. Stay tuned!

Subjects: Practicing, Technique