100 Cello Warm-Ups and Exercises Blog 9: Mentalization and Mimes Part 1

Robert Jesselson

Although I am in China this week and next, I would like to share these two blogs on mental practice – it’s “mind over matter”.

Although I am in China this week and next, I would like to share these two blogs on mental practice – it’s “mind over matter”.

Playing the cello is very much a physical activity. Our ability to play is in many ways governed by how we hold the instrument and the bow. As soon as we take the cello out of the case and sit down our body automatically does what it is used to doing – good and bad. How we shift, or how we do string crossings are built in by habit. We are conditioned to our habitual motions and often don’t even think about how effective they actually are. Even we decide that we want to relearn a physical task, the process is often slowed down by the fact that we keep doing the same old bad habits.

I have found that in learning or relearning a physical task it is often very helpful to do it away from the cello. In part this is because we eliminate what Casals sometimes referred to as his “wooden wife” and we can relearn the motions in the abstract. There are several ways that we can retrain our bodies, including visualization, biofeedback, using a “phantom cello”, and miming.

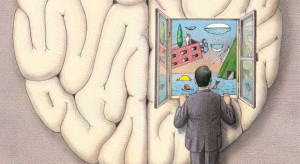

One of the most important techniques is what is called “mental imagery” or “visualization” This involves imagining a task or an activity without actually moving a muscle or completing the action. I like to call this “mentalization”, since much more is involved than just a visual picture. When you “mentalize” a passage of music you hear the music, feel the phrasing, and “play” every note in your imagination. You go through the music in your mind, imagining every step of the way. Your fingers do not actually move and your arms do not actually bow, but you can feel these physical motions. You go through the process in real time, or perhaps even under tempo. If you can do this accurately, you will feel confidence in knowing the piece deeply and securely.

Many athletes use mental imagery to enhance performance. The great golfer Jack Nicklaus referred to this:

“I never hit a shot even in practice without having a sharp in-focus picture of it in my head. It’s like a colour movie. First, I “see” the ball where I want it to finish, nice and white and sitting up high on the bright green grass. Then the scene quickly changes, and I “see” the ball going there: its path, trajectory, and shape, even its behaviour on landing. Then there’s a sort of fade-out, and the next scene shows me making the kind of swing that will turn the previous images into reality. Only at the end of this short private Hollywood spectacular do I select a club and step up to the ball.”

With “mental imagery” it turns out that neurons are actually firing in the same part of your brain as if you were physically moving. Mentalization builds the same neural pathways as actual physical activity, but even more efficiently because there are no wasted motions involved.

When I lived in Freiburg, Germany I used to teach cello in a school near Basel, Switzerland. It was a 40 minute trip on the train, and at first I resented the time that it took to get to the job. One time I took along some music I was working on and “practiced” in my head during the train trip. When I got back to my practice room I discovered that I knew how to play the passages I had “practiced” in my head. It was a great personal discovery about how efficiently and effectively I could learn something by mentalizing it.

Some years later I took the next step. During a summer at Aspen my cello teacher Alan Harris had me learn the Bach Fifth Suite completely away from the cello. I had never played it before, and the assignment was to decide my fingerings and bowings completely away from the cello. I had to figure out the phrase shapes and memorize the piece before I could play a single note on the cello. I could play it at the piano or sing it, or use any other technique I wanted. But I was not allowed to play it on the cello until it was learned and memorized. It was a very difficult assignment, but I ended up learning it faster and more securely than I had ever learned anything before.

The great thing about this technique is that we can do it when we don’t have a cello around – before going to sleep at night, on first waking up, or while jogging. The takeaway is that spending a few minutes warming up with some visualization at the beginning of a practice session is greatly worth the time and effort, and it is more efficient than wasting time noodling while playing. You can’t play out of tune when you mentalize!

In Part Two of this Blog on “Mentalization and Mimes”, I will show a practical example of mentalization, and demonstrate how we can use miming to learn or relearn physical tasks.

Subjects: Practicing, Technique