The Joy of Feuillard – A Sequential Approach to Teaching Bow Technique (Part 10 – Feuillard No. 32 – Variations #22-26)

Robert Jesselson

Part 10 – Feuillard No. 32 – Variations #22-26

With the next several variations we are getting into some specialized strokes that are used for virtuosic playing: the hooked staccato and sautillé . By working on these strokes at this point in their development the students are laying the groundwork for having the ability to use these bowings in pieces in the future . But I feel that they are really important for reasons other than the virtuosic nature of the strokes.

Variations #22-24:

There are four different names for the stroke that is used in Variations #22-24: “up-bow staccato”, “down-bow staccato”, “hooked staccato” and “slurred staccato”. Different people use different terms, and the students should be familiar with all of them. As I explain to the students, these variations are specialty strokes that are used for pieces such as in the Locatelli sonata. I usually demonstrate and ask them to listen to a recording of the Locatelli.

I like to tell them that these are essentially virtuosic strokes, and so they are not very important right now, but then I like to say that they are actually very important right now, emphasizing the irony. I ask them why these variations are really quite important, to see if they understand the main issues: equal bow distribution for all the notes, and the ability to attain the same focused sound throughout the bow so they are capable of playing with that sound anywhere on the bow.

In working on these variations I want to make sure that the students are also observing the difference between the last notes of variations #22 (an eighth note and an eighth rest) and #23 (a quarter note). We need to sharpen their ability to read and interpret accurately what they see on the page.

At the end of this session I again asked Caroline to challenge herself and play it faster (she said that she got it up to 52 here, but it would be good for her to play it much faster in preparation for the real virtuosic up-bow staccato that happens in the literature). This stroke will come back again in Feuillard No. 33 and I hope by that time she will have a good, clean, fast up-bow staccato.

I also mentioned the famous Heifetz Hora Staccato, which was one of his signature encore pieces. This is the up-bow and down-bow staccato par excellence. You can see it here at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mag2mc5Vva0

Variations #25 and #26:

These two variations work with the sautillé stroke. Sautillé means to “hop” or “skip” in French. My working definition of the stroke is that it is a “fast, uncontrolled spiccato”. In other words, it is a bouncy off-the-string stroke, but instead of controlling each bounce, the bow hops off the string by means of its own natural elasticity.

I enjoy teaching sautillé because there are so many different ways to approach it pedagogically. Some students respond to one preparatory exercise, and others respond to other ways of approaching it. Many advanced players have told me that they have a difficult time producing a sautillé stroke. But with the right approach I have found that everyone can create a good sautillé. It just takes finding what works, and then giving it a bit of time and space. Learning sautillé is a multi-week project for most students, and they must be patient through the process.

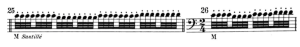

The best overall approach is to slowly creep up to a sautillé before the student even knows it is happening. That happens if they do scales every day with a spiccato bowing, and then every week in the lesson. I start students right away with a slow spiccato at 60 to the pulse doing duplex, triplets, 16th notes, sextuplets and octuplets. By the time they are doing the sextuplets and octuplets in the scale they are already doing a basic sautillé stroke. Sometimes I play the off-the-string scale rhythms in the lessons with the students in thirds:

By doing the scale this way, by the time we reach variations #25 and #26 the students already have a natural approach to playing sautillé without even realizing it. Then it is just a matter of their understanding what they are doing, and knowing how to improve and vary it.

So Caroline has been playing a basic sautillé stroke in her scales for about 2 months, since starting lessons with me. In this next lesson with Caroline, I give her some of the basic information that she will need for improving the stroke.

In the following lesson I asked Caroline to snap her tempo before playing – I find it useful to see if students can imagine the tempo that they have been using in practicing. That insures that they have played enough repetitions at a given tempo, and that they can predict how fast they are supposed to play. It also helps to internalize the tempo before playing it. Caroline played the variation, and then we talked about speeding it up to a goal tempo. Then for the next lesson Caroline increased the tempo.

Up until this point we are still going for the “big picture” here – just trying to play the basic stroke and trying to get the tempo up a bit. We have not yet delved into the details of how to actually improve the stroke. Now we will need to improve the sound, the evenness of the rhythm, the height of the bounce, and one of the main things for creating a good sautillé – finding how to stay out of one’s own way.

There are several exercises that can help students study these various aspects of the sautillé stroke. The first of these is what I call the “bouncy bow” exercise. With this exercise I try to help the student find the natural bounce of the bow. By just letting it bounce from fairly high above the string, the bow will rebound. This is the only time that we start a stroke from above the string – and it is only an exercise. Normally every stroke starts from the string.

We set the metronome at 60 to the pulse, and then do duples, triplets, sixteenth notes, sextuplets and octuplets. This is similar to the ‘off the string’ scale routine mentioned above, but it works differently. We are just exploring the natural bounce of the bow, and we are looking for a ringing, resonant sound.

Caroline had difficulty with this in this lesson. It was hard for her to “let go” and not control the bow. She was pushing down, rather than letting the bow just drop. This video is pretty long – about 8 minutes – because I want to show you how I try to present, analyze and work through the various issues that come up with this stroke. At one point I got up and played it on her cello in order to let her hear how it would sound under her ear. As you will see in the following video, it took another week for her to absorb this information – but at the end she got it.

Another exercise that helps students to understand that the bow has its own bounce is the so-called Bubble Exercise. This exercise demonstrates that the bow has its own natural bounce, and the best thing for us to do is not to do anything! The bow will bounce by itself if we stay out of the way! (the metronome was still going when I demonstrated this exercise! Sorry if that is annoying!)

Another approach to training the sautillé also works with the groupings of 2,3,4,6, and 8 strokes, but this time starting from the string:

In this next video Caroline applied the exercises to the Feuillard #25 and #26. By this time she had increased the tempo up to 65 or so. As always I ask the students to write the tempos that they are doing on the page, so that I can see where they think they are. Sometimes I have to ask them to erase a few numbers and go back to a slower tempo to fix some aspect of the strokes; then they can move it up again.

I remember Paul Katz telling me in a lesson that there isn’t just one type of spiccato or sautillé, but an infinite variety of these strokes, and one has to find the “right” one for any given passage of music. So, this is still a work-in-progress for Caroline. But she now has a good basic understanding of the stroke, which will be further refined several months later when she gets to the Feuillard Theme No 33, Variations #31 and #32 , and then again in the Theme No. 36, Variation #42.

In next week’s blog, we will explore ballistics, and the strokes that combine the upper arm and the wrist. Understanding and executing these circular motions will also help to improve the sautillé stroke.

*If you have questions or comments about The Joy of Feuillard, Dr. Robert Jesselson can be reached directly at rjesselson@mozart.sc.edu.

Subjects: Repertoire, Technique