The Joy of Feuillard – A Sequential Approach to Teaching Bow Technique (Part 17 – Feuillard No. 34 – Basic String Crossing Information)

Robert Jesselson

With this blog we will start working on Feuillard No.34, which focuses on the important topic of string crossings. No. 34 deals with string crossings across two strings; No. 35 is about string crossings across three strings; and No. 36 works on string crossings across four strings. This topic is critical for string players – we work our entire life trying to make string crossings smooth, connected, and ergonomically correct. We try to use the correct parts of the arm, keeping the joints well-oiled and flexible. We try to make the hard bones of our arms look like they are soft and pliable like the “break-dancers” of the 60’s and 70’s. Fluent bow arms are not only beautifully functional, but they are aesthetically pleasing. Think of French cellists such as Navarra, Fournier, or Gendron.

Today’s blog will be rather long because there is a lot of basic information about string crossings that I need to present. This includes some knowledge of the parts of the arm and how they move, as well as an understanding of the four basic bowing figures that we use for all string crossings.

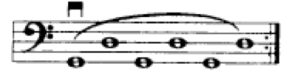

I usually begin working with students on this topic by asking them to play the theme of No. 34 as double stops, making sure that they can identify the intervals. In these videos I will be working with Tristan, who has studied with me for a year and has gone through the earlier pages of the Feuillard (Nos. 32 and 33).

Theme of No. 34:

Next I discuss the four parts of the arm, the joints that connect them, and how the various parts move. I write this information in the student’s notebook to make sure that they can review everything and explain it back to me in the lesson the following week.

There are four parts of the arm, and those parts are connected with different kinds of joints:

- Upper Arm – connected to the shoulder with a Ball and Socket Joint

- Lower Arm – connected to the upper arm with a Hinge Joint

- Wrist – connected to the lower arm with an Articulated Joint

- Fingers – connected to the wrist

Because of these different joints, the four parts of the arm move in different directions:

- Upper Arm – all directions

- Lower Arm – horizontal motions

- Wrist – all directions

- Fingers – vertical motions

The horizontal motions on the cello create all our different strokes: detaché, legato, martelé, staccato, etc. Even in such strokes as spiccato or sautillé, the basic motion is horizontal; the bow bounces off the string because of the flexibility of the bow and the use of the little finger or the wrist.

Based on the information above, three different parts of the arm can produce these horizontal strokes:

- Upper Arm

- Lower Arm

- Wrist

The vertical motions involved in playing the cello produce the string crossings.

Based on the information above, three different parts of the arm can produce these vertical motions:

- Upper Arm

- Wrist

- Fingers

I am always in awe of the “design” of our arms. The alternating “ball and socket” and “hinge” type joints enable us to be able to move in all directions and reach out in space as far as the arm length allows us. At the same time, the design is such that we can use the arm for strength and/or for finely detailed dexterous movements. If we had a “ball and socket” joint at the elbow we would not be able to use our strength to handle heavy tools or press when needed. And our arms are so different from four-legged animals like horses (which don’t have arm-like appendages or ball-and-socket joints) or even other ape-like animals (which don’t have prehensile thumbs). Ah, evolution!

Next we will work on what I call Bowing Figures – these are the four basic shapes that are produced when we do string crossings. All the complicated string crossings that are possible on the cello boil down to four basic Bowing Figures. This is the first one:

So the examples above are all various Arcs. If you reverse bowing direction it creates another arc in a different direction. Some people can imagine these geometric shapes easily, but for some I need to have them actually draw the shapes on a piece of paper while they are playing.

Here is the next Bowing Figure:

So, that was a circular motion. Whether an ellipse or a circle comes out depends on which strings one plays. If you play the G and D strings it produces more of an ellipse. Playing between the A and C strings produces more of a real circle.

Sorry that I was blocking the camera in the last video, but what I did was to put a pencil in Tristan’s hand between his second and third fingers, and then held the pad so that when he played the motion he could see the circle on the paper.

The next figure is:

That was a Figure Eight, or infinity sign. That is often the most difficult one to see at first.

The next is usually the easiest one to visualize:

Next I ask the students to summarize these motions and see what they have in common. When they were first playing these Bowing Figures, some students think that they were seeing straight lines in shapes such as rectangles or squares instead of the curved lines in circles, arcs, figure eights and waves. It is important for them to realize that all of these string crossings are rounded figures.

So, in summary – there are four basic Bowing Figures which are produced in all string crossings in various combinations. They are the Arc, Circle, Figure 8 and Wave.

I made the following pictures with a laser light, demonstrating the four basic Bowing Figures for an article on string crossings in the Strad magazine from September, 2016.

Arc:

Circle:

Figure 8:

Wave:

In next week’s blog Tristan will take me through all the information from this lesson, giving me the “lecture” about the parts of the arm and all the bowing figures to make sure that he has understood and absorbed all the critical material. Then we will begin to go through the Feuillard variations for No. 34.

*If you have questions or comments about The Joy of Feuillard, Dr. Robert Jesselson can be reached directly at rjesselson@mozart.sc.edu.

Subjects: Repertoire, Technique