The Joy of Feuillard – A Sequential Approach to Teaching Bow Technique (Part 23 – Feuillard No. 34 – Variations #26-40)

Robert Jesselson

Today’s variations will work on 16th note rhythm patterns using a detaché stroke with the lower arm and string crossings with the upper arm. The problems are all similar, so the video clips will show Tristan playing just a few measures of each variation. However, during the lesson he played each variation in its entirety.

Variations #26-29:

Variations #30-33:

These variations are similar to the previous ones, but they add bow distribution into the mix. That means we have to try to get the same sound at the frog and the tip. At the tip the main issue will be to use the down bows to get back to the tip each time so that we don’t creep to the middle. It is helpful to use the balance of the left/right motion to get a good sound at the tip, and to stay at the tip.

One issue that I mentioned here to Tristan was not to “pump” each 16th note – in other words not to accent the detaché strokes but rather to connect them.

What you don’t see in these videos is that Tristan (and the other students) will have often played the variations several times in the lesson before getting them more-or-less right on the videos that I am showing. Each time there may have been subtle corrections, even though he had practiced them during the week. At the end of Variation #32 I told Tristan about the need to correct in “real time”. In other words, there is no “perfection” – there is “correction.”

I am reminded of what Carl Flesch wrote in his treatise “The Art of Violin Playing”:

“…In the physical sense, playing in tune is an impossibility. Yet there are a number of violinists who create the impression of playing in tune. How are we to explain this apparent contradiction? By the simple fact that these violinists, though they do not strike the note exactly, do correct it during the fraction of a second, either by shift of position or by means of a vibrato which approximates the true note. All this, when the player is correspondingly skillful, takes place so rapidly that the listener feels as though the note has been true from the very beginning, whereas it has only become so after a tiny lapse of time. Hence what we call playing in tune is no more than an extremely rapid, skillfully carried out improvement of the originally inexactly located pitch…”

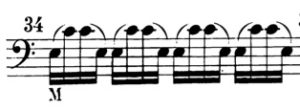

Variation #34 and #35:

These variations are both working on legato string crossings in the middle of the bow. Variation #34 is an Arc, using the upper arm for the string crossings at the tempo that Tristan chose. Variation #35 is a Figure Eight. For this one Tristan chose a faster tempo, and therefore he needed to use more of the wrist and fingers. (The smaller body parts can move faster than the larger parts of the arm).

I notice that some people have more difficulty executing the movement of the wrist going up, while some people have more difficulty going down. In any case, the problem must be addressed and solved so that the wrist moves equally around the core of the arm, going both up and down from the central place. Tristan had problems with the wrist going in the “up” direction earlier, but by Variation #35 it is becoming smoother and rounder.

Variations #36 and #37:

Variations #36 and #37 are both working with the staccato stroke again. In the middle of the bow the upper arm does the string crossing and the lower arm does the staccato. Variation #37 should be played both as hooked staccato and flying spiccato.

Variation #38:

This variation is for bow distribution, left/right motion, and string crossings with the upper arm at both the frog and tip. The student should pay attention to getting a big, core sound at both the frog and tip.

Variations #39 and #40:

The last two variations of Theme No. 34 are both very fast waves, requiring use of the fingers and wrist. By the time they get to these variations, the students will have had experience with several wave variations in No. 34 (#8, #19, and #25) after having explored the bowing figures, the finger and wrist exercises, and the “2,2,2 Waves”. They will have been working on these preliminary exercises for several weeks, and by this time they should be comfortable enough to be able to play the waves fairly fast and evenly with the wrist and fingers. Of course, playing smooth string crossings is a lifetime project for all of us.

Since bow distribution is an important facet of these variations, I usually show the students a good exercise for dividing the bow into 8 parts (for #39) and 16 parts (for #40):

Needless to say, these string crossings are still a “work-in-progress” for Tristan, but with his determination and practice he will continue to improve the accuracy of this technique.

I would like to thank Tristan for allowing me to use these videos with him while he was learning about the important topic of string crossings. He made a lot of progress in his understanding of bow technique during these several weeks.

In the next Blog we will start on Theme No. 35, addressing the issues involved with string crossings over three strings. I will be working with my student Zach on these variations.

*If you have questions or comments about The Joy of Feuillard, Dr. Robert Jesselson can be reached directly at rjesselson@mozart.sc.edu.

Subjects: Repertoire, Technique