The Joy of Feuillard – A Sequential Approach to Teaching Bow Technique (Part 7 – Feuillard #32, Variations 8-11)

Robert Jesselson

Part 7 – Feuillard #32 – Variations 8-11

In watching these videos, you will have noticed that I am continually asking Caroline questions. This is part of the so-called Socratic or Talmudic method of teaching, in which we ask questions rather than just telling the student what to do. The student is encouraged to consider the problem and verbalize a response. I think that this is a really important approach to teaching because we are constantly challenging the students to analyze and talk about what they are thinking. If the students can verbalize something they will understand it better, and it will be lodged deeper in their psyches. And instead of just spoon-feeding information we are helping them to figure out the answers. When students understand how important that is, and start doing this by asking themselves questions in their own practicing, then the progress can be amazing.

The next several variations in No. 32 deal with dotted rhythms, various combinations of staccato strokes, and bow distribution.

Variation #8:

String players are notoriously bad at playing dotted rhythms. It may be somewhat easier for pianists and wind players to play this rhythm accurately because they are not inclined to sustain the ends of the notes. But we string players need to be able to surmount the challenge and be accurate in our playing of the rhythm.

Our tendency is to play dotted rhythms as triplets. The solution to this part of the problem is conceptual: subdividing into either two or four beats. If the rhythm is a dotted quarter note and an eighth note (as in this Feuillard variation) then one should subdivide into two parts, thinking of the quarter notes, or into four parts thinking of the eighth notes. In other words, we have to think “inside the beat” by subdividing. The important thing is not to divide the bow into three parts, since that will produce the triplets that we don’t want.

The next problems are physical: stopping the bow before the short note, and making sure that the short note has enough bow speed and weight so it doesn’t get lost. The energy in a dotted rhythm is on the short note, not the long note.

Variation #8:

I asked Caroline to do it again in the next lesson to make sure that she had really remembered all the information, and to give her some time to absorb the physical things needed to play the dotted rhythms. Feuillard No. 32 has several other dotted rhythm variations further down on the page, so this is just an “introduction” for the student. Later we will refine what needs to be done to play dotted rhythms in a more relaxed manner, and we can address some style issues. But I think it is “brilliant” of Feuillard to have introduced the dotted rhythm concept early on, in order to let a student absorb the basic concepts before digging deeper.

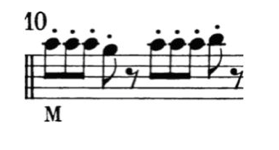

Variations #9 and #10:

These variations work on the staccato stroke again, and are a good way to check up on whether a student remembers some of the earlier concepts that were taught, including using the right part of the bow and arm, the contact point for staccato, and “catch and float”. Number 10 is also interesting in that the rhythm switches between triplets and duples.

Variations #9-10:

As I think I mentioned earlier, I am editing the videos here and cutting them short in order to save time and space in these blogs. However, the students really do play these variations all the way through in the lessons in order to “pass them off” and move on. If the performance is not clean, then they have to do the variation again in the next lesson. I feel that by treating each variation as a performance in the lesson, the students are working on more than just the technique. They are also working on their abilities to concentrate – which is a major issue for young people today.

I had an interesting experience with another one of my pre-college students. He had been having difficulties with memorization and concentration from the very first lesson. I tried lots of different techniques to help him with these issues, but after several months he was not making a lot of progress. Finally one day he came in for his lesson, and his scale and arpeggios were wonderfully memorized and in tune, his Feuillard exercises were magically memorized, he did a great performance of his etude, and his piece had made a big step forward. I was amazed – and asked him “what happened” that he suddenly made such progress in all aspects of his playing. He scratched his head, and said he wasn’t really sure, but he said that he noticed that all of a sudden his school work was better as well. I believe that the work we had done with figuring out how to memorize things, and the concentration exercises we were doing with the Feuillard, and the self-discipline he was learning overall through the cello had a positive impact not only on his cello playing, but also on his school work. And he has continued making great progress in these areas ever since.

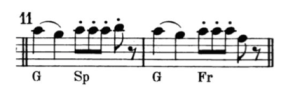

Variation #11:

This variation works on bow distribution, plus staccato at the frog and tip. The idea is to match the sound of the staccato at both ends of the bow. The other main issue here involves the contact point, which needs to be low for both the quarter notes and the staccato notes. However in this case, the contact point needs to be lower for the full bow with two notes, and slightly higher for the staccato notes, demonstrating the concept of “the more notes in the bow, the lower the contact point”. Students have to experiment with this in order to sense what is needed for a good sound.

Variation #11:

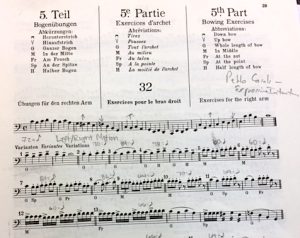

I expect the students to write down the tempos that they think are good for each variation during their practicing. Each variation may have a different tempo. I often ask them to “snap” the tempo before they play, so that I can see if they are imagining their chosen tempo for that variation. Rhythm is such an important basic musical concept, and these variations are helpful in addressing many of the different rhythmical issues, including tempo and pulse. Below is a page from Caroline’s Feuillard exercises, in which she has written the tempos for the variations that she has worked on prior to each lesson. This is also part of the self-discipline that we are training. Notice also the arrows above the notes in the theme (which we discussed in an earlier blog) and Pablo Casals’ term “Expressive Intonation” which I had written in one of the first lessons, so that she is constantly thinking about how the leading tones work in a melodic line.

Next week’s blog will continue with variations dealing with the all-important detaché stroke, as well as other issues involving contact point, bow speed and coordination.

*If you have questions or comments about The Joy of Feuillard, Dr. Robert Jesselson can be reached directly at rjesselson@mozart.sc.edu.

Subjects: Repertoire, Technique